Go interfaces, the tricky parts

Does this Go snippet compile, and if not, why?

package main

func main() {

users := []User{User{"alice"}, User{"bob"}}

// hint: this line compiles, User fulfils Named

var _ Named = User{"charlie"}

getName(users[0])

getNames(users)

}

type Named interface{ name() string }

type User struct{ fullName string }

func (u User) name() string { return u.fullName }

func getName(n Named) string { return n.name() }

func getNames(ns []Named) []string { return nil }It doesn't compile (playground). Surprisingly, although User implements Named, and the getName call is fine, the getNames(users) call is a type error.

When I first came to Go, I found it confusing that, given (1) User implemented Named, and (2) getName(someUser) compiled, that:

- I couldn't pass

[]Useras a[]Named - I couldn't pass

[]Useras an[]interface{} - I couldn't pass

*Useras*Named

Here's a fuller example demonstrating all of these cases.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

users := []User{User{"alice"}, User{"bob"}}

getName(users[0])

// cannot use users (type []User) as type []Named in

// argument to getNames

getNames(users)

// cannot use users (type []User) as type []interface

// {} in argument to countSlice

countSlice(users)

// cannot (type *User) as type *Named in argument

// to switchNamed:

switchNamed(&users[0], &users[1])

}

func getName(n Named) string {

return n.name()

}

func getNames(ns []Named) []string { /* ... */ }

func countSlice(ns []interface{}) int {

return len(ns)

}

func switchNamed(a,b *Named) { /* ... */ }

type User struct {

fullName string

}

func (u User) name() string { return u.fullName }

type Named interface {

name() string

}

Why can't Go be like $language?

It felt inconsistent. It was also very different from languages like TypeScript and Java, where if User implemented Named, as well as being able to pass User to a method accepting Named:

- I could pass

User[]as aNamed[] - I could pass

User[]as anany[](TypeScript only)

For instance, here's the same example in TypeScript (minus switchNamed as TS doesn't have pointers) which compiles and runs without a hitch:

function main() {

const users = [new User("alice"), new User("bob")]

console.log(

getName(new User("charlie")),

getNames(users),

countArray(users),

)

}

class User {

constructor(private fullName: string) {}

name() { return this.fullName }

}

interface Named {

name(): string

}

function getName(n: Named) { return n.name() }

function getNames(ns: Named[]) { return ns.map(n => n.name()) }

function countArray(ns: any[]) { return ns.length }The mystery I wanted to solve was why Go worked exactly the same way in some places (getName(users[0])), but not in others (getNames and countSlice). To solve it I had to learn how Go's interfaces really worked.

Clearing up the mystery

First, an intuition for the difference between interface values and concrete values in Go. Imaging helping your friend move their pets to a new home. They give you two boxes, one labelled 'friendly snakes', one 'fluffy spiders'. Easy enough, sling both boxes in your car and drive! But does that scenario prove you could do the same if they just handed you the critters unboxed? Not at all.

Equivalently, do not assume that because you can store a concrete User in a Named interface value, you can use that concrete value as an interface value. A concrete value and an interface value containing it are fundamentally different things and can be used in different ways.

But if that's true, how is logOne able to accept User values? Simple: the Go compiler automatically creates interface values for you where it can. The two lines below are equivalent:

// Go implicitly allocates an interface value and places the User in it

logOne(User{"charlie"})

// ...equivalent to us manually allocating one and passing it

var f1 Named = User{"charlie"}

logOne(f1)What interface values are really

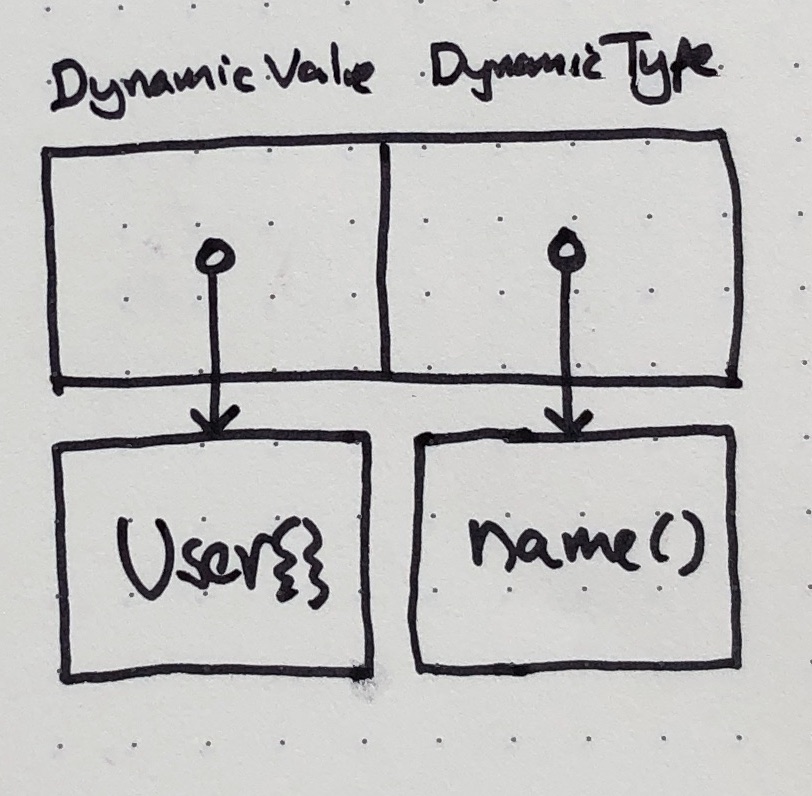

Let's make it concrete by considering what these 'boxes' look like. Go's interface values are really a pair of pointers. When you put a concrete value into an interface value, one pointer starts pointing at the value. The second will now point to the implementation of the interface for the type of the concrete value. They're called the dynamic value and the dynamic type respectively - dynamic because both are set at runtime when we assign concrete values into an interface value.

This pair of pointers is the secret to how Go's interfaces work. When a method is called on an interface value, Go follows the implementation pointer to find the appropriate method and the value pointer to be able to use the value as the receiver (or it panics if the 'box' is empty: a nil value). Thus you can see why code that works with an interface value really cannot work on concrete values alone.

The slice inconsistency

A check on your understanding: why can't we pass a []User as a []Named? Try to think through what the two slices/backing arrays would look like in memory.

Answer

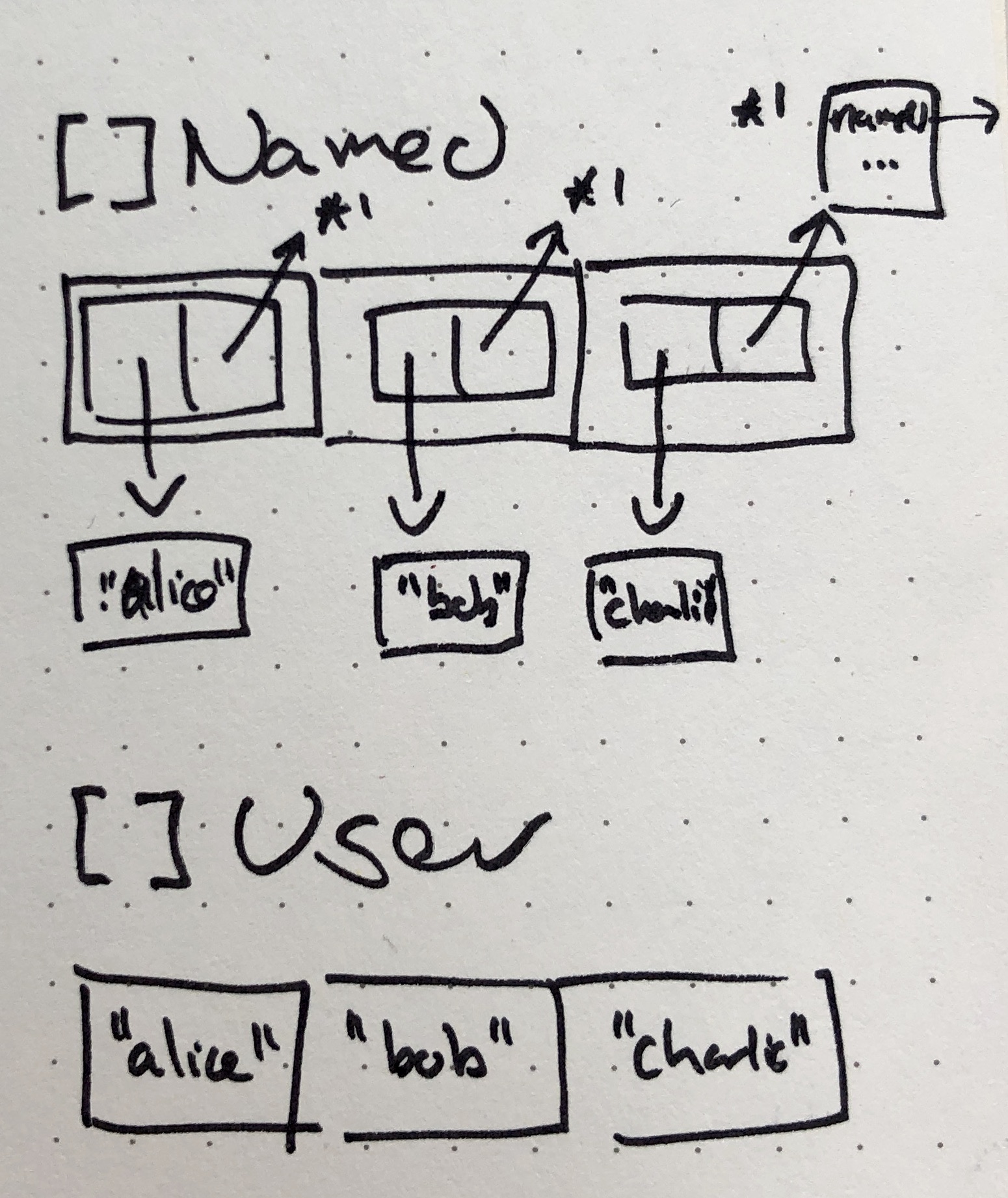

The crux is again that an interface value is a different thing to a concrete value, rather than - as in other languages - just another way a concrete value can be used. Each cell in a slice of interface values will contain one of those familiar double pointer values:

However, given Go can automatically allocate a Named where required, couldn't Go also allocate a []Named automatically to let you pass a []User to getNames? It's certainly possible to imagine how Go could do it. It could allocate a new slice of interface values for you, and assign the concrete User values into corresponding indexes:

users := []User{User{"alice"}, User{"bob"}}

// below is what Go would have to do to make switchItems(users, 0, 1) work implicitly

ns := make([]Named, 0, len(users))

for _, u := range users {

var n Named = u

ns = append(ns, n) // *

}

getNames(ns)Indeed, for getNames(users) this would actually work fine! But slices have mutable indexes. and many functions mutate the slices they're passed. Can you see why automatically creating new slices to pass in would not work as desired for such functions? For instance:

func switchItems(xs []Named, a, b int) {

t := xs[a]

xs[a] = xs[b]

xs[b] = t

}

users := []User{User{"alice"}, User{"bob"}}

// not possible, but imagine it was and Go did the implicit

// allocate/initialize we did above

switchItems(users, 0, 1)The implicit allocation would stop switchItems from working as we'd only be affecting the newly allocated slice/backing array - ns in the example above where I showed you what Go would have to do to make it work.

Again, Go's helpful implicit conversions can make this confusing. In the loop above where we create a []Named from a []User, the var n Named = u is unnecessary, we could just do append(ns, u /* u is a User value */). Now we know that's because Go can safely, and implicitly, create the required interface value for us.

Takeaways

If get a type error when you attempt to use a concrete value in a place needing an interface value and you think "but it fulfils the interface", remember: interface values and concretes are very different things. That you can place a concrete value in an interface value does not mean it is an interface value, so you can't use it in all the same ways.

For instance, if you have a function accepting []interface{} you can't pass a slice of concrete values. Although we know all interfaces fulfil the empty interface, an interface value is still different from a concrete value: it's a container which allows us to peek in and extract the concrete type via type assertions. So if we have a slice of concrete values we're going to have to allocate interface values to pass in:

func findAndRemoveUsers(xs []interface{}) {

for i, x := range xs {

if _, ok := x.(User); ok {

fmt.Println("There is a user at", i)

xs[i] = nil

}

}

}

users := []User{User{"alice"}, User{"charlie"}}

// could just as well be []interface{}

ivs := make([]Named, 0, len(users))

for _, u := range users {

ivs = append(ivs, u)

}

findAndRemoveUsers(ivs)

// double check it's clear to you why this couldn't be

// supported automatically - consider xs[i] = nil

findAndRemoveUsers(users)Quiz time

Why couldn't Go do something clever to let us pass a pointer to a User to a method accepting a pointer to Named?

func switchNamed(a,b *Named) {

t := *a

*a = *b

*b = t

}

u1 := User{"alice"}

u2 := User{"bob"}

// type error

switchNamed(&u1, &u2)Spoiler

Much like with the slice example above,switchNamed(&u1, &u2) to work Go would have to automatically allocate an interface value. If it did, and passed that into the function, assignments to that fresh *Named would have no affect on the original *User, and so no visibility outside the function. So instead it's a compile-time type error:

// this compiles fine

var n1 Named = User{"alice"}

var n2 Named = User{"bob"}

fmt.Println(n1, n2) // {"alice", "bob"}

switchNamed(&n1, &n2)

fmt.Println(n1, n2) // {"bob", "alice"}

//

// going back to our example...

u1 := User{"charlie"}

u2 := User{"denise"}

fmt.Println(u1, u2) // {"charlie", "denise"}

//

// ...which wouldn't compile because 'can't use type *User as *Named'

// switchNamed(&u1, &u2)

//

// ...we can figure out that if the Go accepted it by implicitly generated new *Named values

// for the &u1, &u2 passed to the method, e.g. like equivalent to the n3/n4 code below...

var n3 Named = u1

var n4 Named = u2

switchNamed(&n3, &n4)

// ....we'd end up with the code not working as expected: u1 and u2 would be unaffected!

fmt.Println(u1, u2) // {"charlie", "denise"}

Note: pointers to interfaces are fairly rare in practise.

Thanks to Campbell Morgan, Iheanyi Ekechukwu and Stephen Bradshaw for reviewing this and offering their wisdom!

It appears that the final code sample (quiz time) have a small error unrelated to the topic at question. Not enough arguments are passed to `switchNamed`.

Thanks for spotting @Streppel! Fixed 🙌

Leave a comment via Github 💬